A platform that encourages healthy conversation, spiritual support, growth and fellowship

NOLACatholic Parenting Podcast

A natural progression of our weekly column in the Clarion Herald and blog

The best in Catholic news and inspiration - wherever you are!

At age 74, Bissant continues to enjoy the game he loves

-

By Ron Brocato, Sports

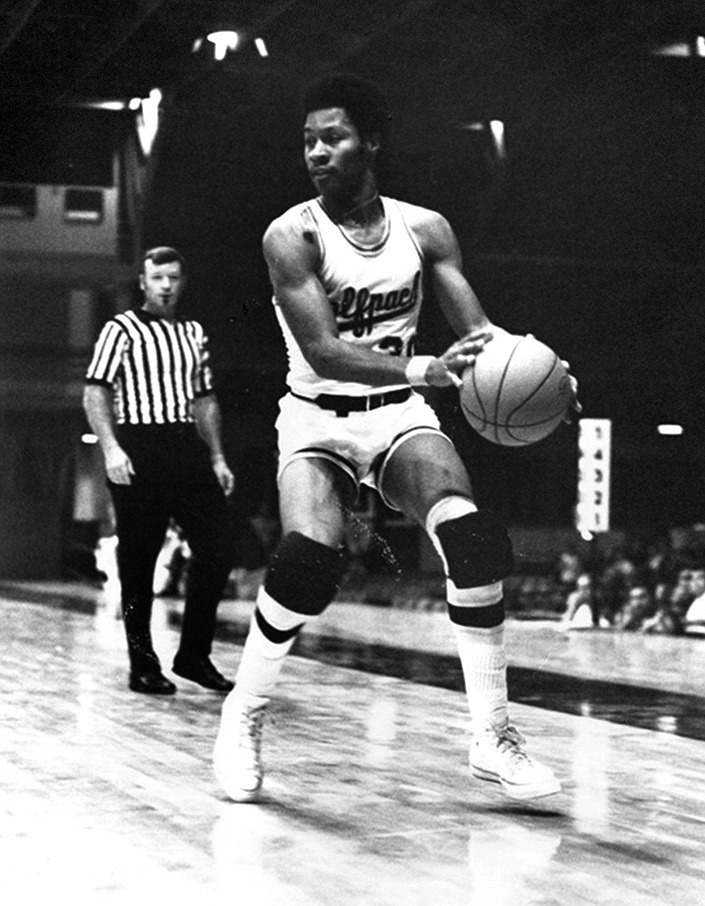

Clarion HeraldBobby Bissant is 74 years old.

He loves the game of basketball. He’s played and excelled at the sport, both at Xavier Prep and Loyola University.But Bissant doesn’t get to enjoy the game as a spectator very often these days because he’s still officiating the game he loves at the high school level. Yes, those 74-year-old legs are still strong enough for this referee to lift them to eye level and stretch his hamstrings before joining his crew to run through 32 minutes of basketball action.

“I keep telling Chuck Dorvin to give me easy games, but he still sends me to games in the upper classes,” Bissant said.

That’s because Dorvin, the assignment secretary for the local high school officials association, recognizes Bissant’s ability and reputation as a top-drawer referee, but partly because there is a shortage of high school basketball officials throughout the LHSAA.

There is no doubt Bissant has the credentials. He has worked games in the Big 12, Conference USA, Gulf Coast Athletic Conference and the Southland Conference over the decades and continues to observe and grade officials as part of a consortium that includes the Big 12 and Southeastern Conferences.

He’s had an even more interesting career as an athlete.

Bissant’s father barnstormed as a player in the Negro Leagues until his son was born.

Like his father, young Bobby wanted to be a baseball player: “I would come home with bumps and bruises on my face and thought, ‘I need a bigger ball,’ and threw down the glove and bat. Then I put up a crate in the back yard and started shooting a basketball.”

He returned home from school one day to see a basketball goal set up in the front yard. Bissant and the Magnolia neighborhood boys honed their skills on that goal. And Bobby developed quickly and had to think about high school.

“I thought about going to St. Augustine but decided on Xavier Prep to be around the girls,” he said with a smile. “And, I thank Almighty God, St. Katharine Drexel and the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament that started schools to help black people and Native Americans get an education.”

Bissant’s athletic abilities became apparent in 1965-66, the first season that black Catholic schools were invited to play in the CYO Tournament. His Xavier Prep team and St. Augustine broke the color line.

Although Xavier Prep lost its one-and-done game to Jesuit, 83-75, Bissant impressed the 4,000 spectators at the Loyola Field house. The following year, Xavier lost again to De La Salle, 71-56, but Bissant scored 30 points. Meanwhile, St. Augustine defeated De La Salle, 56-50, to take home the championship trophy.

His senior year of 1966-67 was the waning years of all African-American LIALO (the black twin of the LHSAA), the “Baron” of Kentucky, Adolph Rupp, recruited him to be the first black player for the Wildcats.

“He tried to get me the year after they lost the NCAA championship to Texas Western,” Bisssant said.

Texas Western, the No. 3-ranked team in the country in 1965-66, had an all-black starting roster and was coached by Don Haskins. There were no black players on the No. 1-ranked Kentucky team. Both had identical 37-1 records entering the title game, but Rupp’s Wildcats trailed from start to finish and lost, 72-65.

Rupp was apparently looking for young, black players, whose talents were proliferating throughout college and professional sports. Bissant sensed Rupp’s bigotry and motives by reading about him and respectfully declined the scholarship offer.

Through noted Newman coach Ed Tuohy, who had a connection in New Mexico, Bissant received a scholarship to the University of Albuquerque, where he played for two years before the college folded its athletic program.

Tuohy and Loyola’s athletic director, Louis “Rags” Scheuermann, brought him home and enrolled him at the Catholic university, where he recorded a 21.6 scoring average and was drafted by the Chicago Bulls of the NBA and Indiana Pacers of the ABA after the 1970-71 season.

Among Loyola’s opponents in 1970-71 was LSU. Bissant recalled, “I watched film of Pete Maravich when they played Loyola the previous year. Pete was shooting (what would become years later) 3-pointers from almost half-court. I said, ‘Nobody’s guarding this guy.’”

That was because Maravich was calling screens from his team’s tallest players, “Apple” Sanders and Bill Newton, around which he’d get free for a shot.

“If you tried to block his shot, he’d throw a pass behind his head or between his legs to a player in full stride to the goal,” Bissant said. “Just fabulous!”

“If you tried to block his shot, he’d throw a pass behind his head or between his legs to a player in full stride to the goal,” Bissant said. “Just fabulous!”LSU won the game, 100-87, with “Pistol Pete” scoring 45 points. But Maravich's defensive efforts were no match for Bissant’s speed and maneuverability. He poured in 32 points of his own.

The 1971 draft included such college stars as Austin Carr, Sidney Wicks, Elmore Smith, Artis Gilmore, Curtis Rowe and Spencer Haywood, and there was a tug-of-war between the NBA and rival American Basketball Association.

The Bulls selected Bissant in the 16th round as the 229th pick, but he made the mistake of signing with Indiana.

“The Pacers lured me away from the NBA by giving me a little money when I didn’t have a dime,” he noted. “They cut me around Thanksgiving. They had players like George McGinnis, Mel Daniels, Darnell Hillman, Freddie Lewis and Bob Netolecky. I found out that I couldn’t make the team because all the veterans had no-cut contracts.”

So, it was off to Europe, where Bissant played for Amsterdam and then a team in Salzburg before giving up his dream to play professionally.

“I made between $35,000 t0 $40,000, plus I had incentives,” he said. “My apartment was paid for, and they gave me a car and a round-trip ticket home in case a war broke out. I had a good time and came home with quite a nestegg.

“I moved to California at age 25 when the Lakers called me to play in their summer league, but that didn’t work out, so I got a job in the (San Fernando) Valley as an assistant supervisor. There was a new park opening, and I took a part-time job with the park superintendent.”

That turned out to be a life-changing experience.

“One day a man tells me, ‘Bobby, the referees didn’t show up. I need you,’” Bissant recalled. “I told him that I didn’t know anything about officiating. He said, ‘You played; you must know something.’”

That was the beginning of a career that has carried on through nearly six decades of high school and junior college games and four college conferences, starting with the Big West Conference. And it now runs in the family.

“My cousin, Derrick Collins, is an NBA official, and my son is in Grand Rapids working an NBA G League game. He’ll fly in to work a UNO game. I still do Dillard, Xavier and William Carey games, and I'm in my third year of high school games. But they went much further than I did,” he chuckled.

That’s doubtful, Sir!