A platform that encourages healthy conversation, spiritual support, growth and fellowship

NOLACatholic Parenting Podcast

A natural progression of our weekly column in the Clarion Herald and blog

The best in Catholic news and inspiration - wherever you are!

Explaining ‘science’ of COVID to teens

-

By Christine Bordelon

Clarion Herald

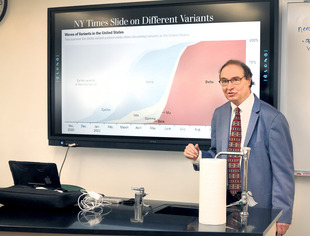

Teen girls taking Archbishop Chapelle’s biology, physiology and environmental science courses had a diversion from regular classes recently when Dr. Brian Credo presented a COVID Omicron variant lesson plan, complete with sparkling grape juice and chocolates. “The lesson teaches what a variant is, what makes this one different, and how to calculate the ‘R Naught’ transmissibility factor (basic reproduction ratio),” said Credo, associate professor of clinical pediatrics at Tulane School of Medicine and director of the Bio-Med track in the pre-professional program at Archbishop Rummel High.

“The lesson teaches what a variant is, what makes this one different, and how to calculate the ‘R Naught’ transmissibility factor (basic reproduction ratio),” said Credo, associate professor of clinical pediatrics at Tulane School of Medicine and director of the Bio-Med track in the pre-professional program at Archbishop Rummel High.He said the coronavirus is a topic in which his Rummel students were interested. He knew others would be, too.

Falling down a ‘rabbit hole’

Credo illustrated the indomitable human spirit when bad things happen by reading a poem, “Invictus,” written by William Ernest Henley, a dying patient. It reminded him of “Alice in Wonderland,” who falls down a rabbit hole and enters an altered reality.“That’s what the pandemic has made people feel like,” Credo said.

Demonstrating that they were not alone, he showed a short film, “Cocoon,” detailing how children in Portland, Oregon, were dealing with being quarantined – not knowing what day it was, missing friends, teachers and school. Chapelle students laughed when Portland students said they ate more junk food and were going crazy at home with siblings 24/7.

“The pandemic has affected people in a lot of different ways and has been challenging,” Credo told them.

When identified in the U.S. in March 2020, the virus was labeled “coronavirus” until November 2020, when variants were named.

A New York Times slide detailed the variant waves in America and their mutations into new variants such as Epsilon, Iota, Gamma, Beta, Mu, Delta and the current Omicron variant, which has been more transmissible but less deadly to most people, he said.

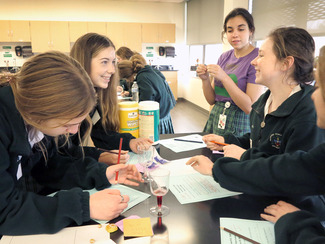

Credo divided the girls into two groups. One drank sparkling cider and were called ministers of champagne and were asked to write encouraging words to classmates on sticky notes.

Credo divided the girls into two groups. One drank sparkling cider and were called ministers of champagne and were asked to write encouraging words to classmates on sticky notes.The others – called ministers

of chocolate – heard him discuss different variant characteristics and explain that a variant is “a group of coronaviruses that share the same inherent set of distinctive mutations.”

of chocolate – heard him discuss different variant characteristics and explain that a variant is “a group of coronaviruses that share the same inherent set of distinctive mutations.”

He decoded how spike proteins in viruses hijack living cells and replicate. Vaccines target spike proteins.

He decoded how spike proteins in viruses hijack living cells and replicate. Vaccines target spike proteins.“If we can stop the spike proteins from anchoring in, then we can stop the virus from getting in your cells and replicating,” he said.

Credo cited the effectiveness of different masks according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Wearing N95 and KN95 masks lowered the chance of testing positive by 83%, surgical masks by 66% and cloth masks by 56%.

“Every mask is not the same,” he said.

The groups switched, and the ministers of champagne learned that the CDC plans to detect coronavirus in wastewater since “40 to 80% of people infected with coronavirus can shed viral genetic material in their feces even before they show any symptoms.”

Viral material in wastewater generally appears four to six days before a rise in cases or hospitalizations. This data is not affected by access to health care or availability of clinical testing, “making them uniquely powerful,” although it’s a better barometer in smaller towns as opposed to larger ones.

“This could be a fascinating way to get data,” he said, to help the health system control the spread.

Credo also explored the “R naught” factor – how we measure transmissibility – the number of people an infected person can spread the virus to, and how a person’s contact factor affects transmissibility.

“I enjoyed the lesson a lot,” said Chloe Mathes, 17. “It made me see the more scientific side of it. A lot of times when people speak about the virus, they don’t know a lot about it. It is good to hear someone who knows facts.”

Continue sharing

During the pandemic, Credo began a collaboration with Catholic high schools and parents to address teen depression and anxiety in the talk “Raising a Teenager During Pandemic Time.” It was so well received that he created this talk for any Catholic school seeking to clarify for students what a virus variant is.“Having experience with a practicing physician as their teacher is valuable,” said Danielle Rohli, Chapelle science teacher and dean of academics, who monitored the talk. “He is a specialist in the field, and it’s better to ask questions of him than someone not in the medical field.”

Credo, a product of Catholic schools, encourages schools to share knowledge.

“It just seems like our schools can be so much stronger when we work together and help each other,” he said. “Catholic educators nurture the body, mind and soul of students,” and teach the light of Christ to students.

He decoded how spike proteins in viruses hijack living cells and replicate. Vaccines target spike proteins.

“If we can stop the spike proteins from anchoring in, then we can stop the virus from getting in your cells and replicating,” he said.

Credo cited the effectiveness of different masks according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Wearing N95 and KN95 masks lowered the chance of testing positive by 83%, surgical masks by 66% and cloth masks by 56%.

“Every mask is not the same,” he said.

The groups switched, and the ministers of champagne learned that the CDC plans to detect coronavirus in wastewater since “40 to 80% of people infected with coronavirus can shed viral genetic material in their feces even before they show any symptoms.”

Viral material in wastewater generally appears four to six days before a rise in cases or hospitalizations. This data is not affected by access to health care or availability of clinical testing, “making them uniquely powerful,” although it’s a better barometer in smaller towns as opposed to larger ones.

“This could be a fascinating way to get data,” he said, to help the health system control the spread.

Credo also explored the “R naught” factor – how we measure transmissibility – the number of people an infected person can spread the virus to, and how a person’s contact factor affects transmissibility.

“I enjoyed the lesson a lot,” said Chloe Mathes, 17. “It made me see the more scientific side of it. A lot of times when people speak about the virus, they don’t know a lot about it. It is good to hear someone who knows facts.”

Continue sharing

During the pandemic, Credo began a collaboration with Catholic high schools and parents to address teen depression and anxiety in the talk “Raising a Teenager During Pandemic Time.” It was so well received that he created this talk for any Catholic school seeking to clarify for students what a virus variant is.“Having experience with a practicing physician as their teacher is valuable,” said Danielle Rohli, Chapelle science teacher and dean of academics, who monitored the talk. “He is a specialist in the field, and it’s better to ask questions of him than someone not in the medical field.”

Credo, a product of Catholic schools, encourages schools to share knowledge.

“It just seems like our schools can be so much stronger when we work together and help each other,” he said. “Catholic educators nurture the body, mind and soul of students,” and teach the light of Christ to students.