A platform that encourages healthy conversation, spiritual support, growth and fellowship

NOLACatholic Parenting Podcast

A natural progression of our weekly column in the Clarion Herald and blog

The best in Catholic news and inspiration - wherever you are!

St. Roch Chapel eager to debut its dazzling overhaul

-

Above: The tabernacle at St. Roch Chapel features its original paintings of angels. A faded and tattered portrait of Jesus wearing a crown of thorns was discovered inside the tabernacle and has since been restored (photo below). The tabernacle is one part of the chapel’s retable (photos below), which was in total disrepair due to flooding and termite infestation. The entire piece was restored and returned to its original location atop the altar. (Photos by Frank J. Methe and Beth Donze, Clarion Herald; and courtesy of New Orleans Catholic Cemeteries)

By BETH DONZE

Clarion Herald

Built in gratitude for St. Roch’s intercessory protection during the era of yellow fever, the tiny Gothic chapel that rises out of St. Roch Cemetery No. 1 has endured hurricanes, floods, termites and padlocked doors in its 145 years of existence.Now, in the midst of yet another public health crisis, the iconic structure – which underwent a stunning restoration of its interior by New Orleans Catholic Cemeteries (NOCC) – is set to resume its role as a much beloved holy space.

St. Roch Chapel will formally reopen next year, following a rededication and prayer service to be led by Archbishop Gregory Aymond. Although a firm date has yet to be set for the ceremony, Sherri Peppo, executive director of New Orleans Catholic Cemeteries, is confident the event will happen within the next several months, as decreasing cases of COVID-19 permit the faithful to safely assemble once again in the small chapel space.

“We not only wanted to bring the chapel back to its original physical appearance, we also wanted to return it to its original purpose as a space of healing and prayer,” Peppo said. “This restoration will allow us to do both.”

Walls can ‘breathe’ nowThe overhaul, launched in 2017, involved a complete restoration of the chapel’s 324-square-foot nave and vaulted ceiling, which peaks some 30 feet above the marble floor.

Interior walls, which were bowing due to their framework of bricks mortared in moisture-trapping Portland cement, were an early focus of the work, Peppo said. After removing a layer of aluminum paneling that had been “wallpapered” over the walls at some point in the chapel’s history, the newly exposed bricks were repointed, re-plastered and painted with breathable, lime-based products.

“When we stripped the walls down to the brick, the bricks were very wet. We had to let them dry for three to four days – they had been holding moisture for years,” recalled Peppo, who oversaw the restoration with project manager Joseph Connor, New Orleans Catholic Cemeteries’ assistant director of operations.

Stripping the walls down to the bricks also enabled the craftsmen to remove termite-infested frames around the chapel’s 11 arched windows and to install all new electrical wiring. The restored interior touts both natural and artificial illumination, thanks to spotlights, recessed lighting in the ceiling and four gas lanterns, the latter original chapel fixtures now safely refitted to operate on electricity.

Stripping the walls down to the bricks also enabled the craftsmen to remove termite-infested frames around the chapel’s 11 arched windows and to install all new electrical wiring. The restored interior touts both natural and artificial illumination, thanks to spotlights, recessed lighting in the ceiling and four gas lanterns, the latter original chapel fixtures now safely refitted to operate on electricity. The restoration also addressed vaults located inside lower walls of the nave. New Orleans Catholic Cemeteries reconfigured these recesses into 36 double-niches available for the in-chapel interment of cremated remains.

The restoration also addressed vaults located inside lower walls of the nave. New Orleans Catholic Cemeteries reconfigured these recesses into 36 double-niches available for the in-chapel interment of cremated remains.Intricate retable restored

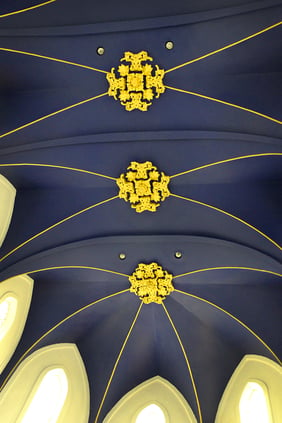

Peppo said the chapel’s ribbed ceiling, featuring three ornate plaster medallions, was in relatively good shape and only required a good cleaning. It was repainted in an eye-popping hue of midnight blue with gold accents.

Eight pews, salvaged from a decommissioned church in the northern U.S., and a 19th-century, French-carved statue of St. Roch, procured from an antiques shop in Texas, are among the chapel’s “new” furnishings.

Another piece of furniture likely to catch the eye of those who enter is the chapel’s seamlessly refurbished retable – the architectural term for the shelved unit above a church’s main altar that features decorated panels and niches for sacred objects. Ravaged by termites and six feet of water in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, whole segments of the African mahogany, Spanish cedar and cypress retable were literally vanishing, Peppo said. The unit was disassembled and taken to third-generation master carpenter Juan Montoya for restoration and replication of missing features such as finials, floral medallions and spindlework.

Now returned to its original location atop the marble altar, the retable celebrates its saintly connections with folding cabinet doors holding six painted scenes from the life of St. Roch, painted by Italian-born, New Orleans resident Renato de Guzman in 1949.

Now returned to its original location atop the marble altar, the retable celebrates its saintly connections with folding cabinet doors holding six painted scenes from the life of St. Roch, painted by Italian-born, New Orleans resident Renato de Guzman in 1949.The restoration of the retable also uncovered a treasure hidden away for decades. When Connor opened the angel-painted cabinet that once housed the tabernacle, he found a torn and faded portrait of the suffering Jesus wearing a crown of thorns. Carefully restored by Italian-born art conservator Alessia Filetti, the painting will be brought to the chapel for the rededication, future Masses and other special events. To protect its integrity during non-Mass times, a high-quality reproduction will stand in its place, Peppo said.

Two other interior features – the pair of small, grotto-like rooms accessed through flanking doorways near the altar – were treated differently in the restoration. The famous room containing ex-votos (tokens such as cast replicas of limbs, leg braces, crutches and children’s shoes in gratitude for St. Roch’s healing intercession) was left in its original state; the other room, which has been returned to its original function as a sacristy in which priests can vest for Mass, had its walls re-mortared, re-plastered and painted with lime wash, Peppo said.

Ringing in a new chapter

Although the exterior of the hexagon-shaped chapel was not a focus of the restoration, a new roof of standing seam copper now protects the structure from water intrusion. Leaks over the decades had caused rot and termite infestation in the attic, and, if left unaddressed, put the ceiling in danger of collapse, Peppo said.

Steel beams now stabilize the attic and form the new framework for the chapel’s original bronze bell. The restored bell, whose overhaul was funded by a grant from the Stella Roman Foundation, can now be seen through a semi-circular opening at the top of the chapel, thanks to the removal of a vent that was also masking two ornamental gargoyle carvings.

Historic landmark status

A rededication plaque listing the names of 66 individuals and entities who donated $200 or more to the chapel’s restoration fund will be unveiled at the future rededication ceremony, Peppo said. Donations earmarked for specific items included funds from an anonymous donor to restore the retable, and monies used to purchase a new statue of St. Roch – a gift from Lynda Moreau in memory of deceased members of the Moreau-Walgamotte families and their “beloved dogs.” Moreau also donated a first-class relic of St. Roch that will be displayed during Masses and special events.

Peppo is proud that the restoration did not cut corners but rather called on craftsmanship and products that will sustain the structure, a Local Historic Landmark since 2002, for the next hundred years.

Peppo is proud that the restoration did not cut corners but rather called on craftsmanship and products that will sustain the structure, a Local Historic Landmark since 2002, for the next hundred years.“We followed the Secretary of Interior standards for historic restoration projects, as outlined by the National Park Service,” she said.

Place of pilgrimage

The chapel, which also holds the designation of being the National Shrine of St. Roch, is named for the Third Order Franciscan who devoted his life to caring for victims of the bubonic plague and was credited with miraculous cures. Born in 1295 in Montpellier, France, St. Roch is the patron saint of the sick, invalids, dogs and dog lovers.

When faced with another “plague – yellow fever – in his own time, Father Peter Leonard Thevis, pastor of German-Catholic Holy Trinity Church from 1868-93, asked his parishioners to pray to St. Roch to spare them from the epidemics that were intermittently visiting New Orleans. In gratitude for a lull in the outbreaks, Father Thevis’ flock erected the chapel in 1876 as a monument of gratitude to St. Roch, burying their beloved pastor under the chapel floor upon his death in 1893.

Unfortunately, yellow fever continued to wreak havoc in New Orleans, with 41,000 dying from the disease between 1817 – the first year records were kept – through 1905.

Subsequent decades saw the faithful pack the chapel for funerals, Masses and prayers for healing, with many of them leaving ex-votos in thanksgiving for being cured.

Subsequent decades saw the faithful pack the chapel for funerals, Masses and prayers for healing, with many of them leaving ex-votos in thanksgiving for being cured.Use of the chapel began to dwindle as parishioner numbers at Holy Trinity declined (the church closed permanently in 2001) and the growing availability of Masses at nearby Our Lady Star of the Sea, which opened a new and much larger church in 1931.

To be in service once again

To safeguard its fragile historic interior, the chapel will only be open for Masses and special events, Peppo said. NOCC will coordinate with local priests to schedule a monthly healing Mass at the site, and the space also will be made available once again as a mortuary chapel for those being interred at the cemetery.

Throughout the four-year restoration project, the surrounding cemetery grounds have continued to attract those who have loved ones buried there as well as visitors drawn by the site’s history and architectural beauty. A COVID-safe “virtual run,” held for the past two years, elicited participation from across the United States and Europe. The most recent Good Friday walking Stations of the Cross – to 14 cemetery statues depicting Christ’s passion – drew more than 200 faithful and gave NOCC an opportunity to test the chapel’s newly restored bell.

For updates on this story or to inquire about burial options inside St. Roch Chapel, call (504) 596-3050; email [email protected]; or visit nolacatholiccemeteries.org. Website visitors can also sign up to receive New Orleans Catholic Cemeteries’ digital newsletter.